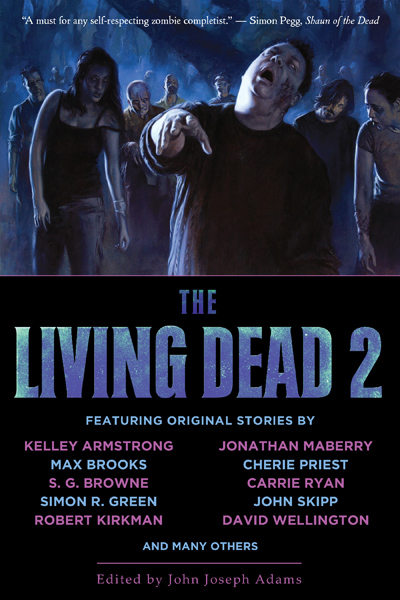

We hope you enjoy this short story from The Living Dead 2, edited by John Joseph Adams.

* * *

The sun was coming down over the desert, painting the red rocks a hundred different shades of purple, silver, and ocher and making spiky silhouettes out of the few creosote bushes that eked a living out of the barren land. I watched the hot pink clouds scud by overhead for a while before turning my attention back to the fence.

Then my heart stopped beating.

The dead man was only a couple feet away from Candy when I saw him. He was on the wrong side of the chain-link fence but he was leaning on it, hard, and it was starting to sway. His clothes were bleached white by the sun and his skin was gray. His lips had rotted away, like most of his face, and his teeth were huge and yellow and broken until they looked very sharp.

Candy was three years old. She didn’t even look up. There’d never been a time in her life when the dead people weren’t around, weren’t reaching for her, gnashing their teeth at her. There’d never been a time when Mommy wasn’t right there to save her.

I wasn’t going to let her learn different. Not until she was old enough to hold a weapon.

So I didn’t shout at her, didn’t scream for the dead guy to back off. I brought up my bow and nocked an arrow. Drew back, nice and steady, and took my time to aim. My bow string twanged but my arrow didn’t make a sound as it went right through the chain link, and right through his skull. The point came out the other side.

He fell down in a heap. Silently.

Thank you, Girl Scouts of America, I thought.

I went over to Candy then, to get her away from the corpse. They don’t smell so bad anymore—the sun down here dries them out—but you can still get sick just by being near them. And sometimes they aren’t as dead as they look.

Candy was squatting down on the ground by the pump house that used to fill up the swimming pool. She had a bunch of credit cards and she had laid them out on the yellow grass, sorting them by color. The plastic had gone white around the edges over time and the silver ink had rubbed off the numbers, but the holograms still flashed back and forth in the sun as I reached down to pick her up.

“Look at the bird,” Candy said, pointing at one of them. “It flies if you close one eye, then the other.”

“Sure does, pumpkin,” I said, and kissed the side of her head.

It’s been a year and a half since I saw a bird. I don’t know when she ever had, but she knew, birds fly. Birds fly away. People have to stay on the ground, right where they are.

Bruce and Finster came out of the shade of the motel complex wearing gloves and bandanas across their faces. I covered them with my bow while they dragged the corpse into the empty pool and set it on fire. The bottom of the pool used to be painted blue but the paint had chipped away months ago and now the bare concrete showed through. There were black scorch marks like flat craters all over the concrete.

The guys couldn’t just drag the body out into the desert to rot away. That would just draw more of the dead—they don’t eat their own kind, but once you destroy the brain, all bets are off. Anything that could hurt us, anything that would draw attention to us, was dragged down into the pool and burned until there was nothing left but ashes and bones.

I didn’t stick around to watch. I took Candy back to our room instead, to let her play inside where the air might be stuffy but she couldn’t just wander away. Then I went into the dark bathroom and stared at myself in the mirror for a while.

I did that every time I killed somebody. I was looking for any sign of fear, or weakness. If I found my lips were shaking I made them stop. If my eyes looked too wide I forced myself to squint. If I had gone white as a sheet I held my breath until my color came back.

I could have been an actress. You know, Before. I was a dancer in Vegas—yes, that kind of dancer—but I was saving my money to go to LA. Then it got overrun and everybody there died. Guess it was a good thing I never got my big break. This time, when I stared in the mirror, I didn’t see anything looking back. My face was there, my cheekbones more hollow than they used to be, lines around my eyes a little deeper. Blond hair bleached by the sun. I looked even skinnier than I used to when I was dancing. But there was nothing there in my face, no expression at all.

I wondered if that was a bad thing. If that was worse than finding signs of weakness there.

Then I decided that was a stupid thing to worry about. Times like these, you learned pretty fast what was important and what was bullshit, and you let the bullshit go.

The rules were that when you even see a dead guy, you had to tell Vance. I headed out, leaving Candy alone where I knew she was safe, and walked down the row of motel rooms toward the reception office, the place he was most likely to be. As I stepped in through the glass doors I found about half of the survivors there. It was the stuffiest part of the motel, and there were no curtains on the windows so the desert light came glaring in, but ever since the dead came back people tend to want to congregate in central places where they can see each other, so reception is always crowded. There were old folks logging in cans of food from the last foraging expedition, and young guys bristling with weapons, just standing guard. Good people, all of them. I’ve known plenty of the other kind, but we left all of them behind.

Of course Simon was there, tinkering. Just like always. Simon was the only one of us who couldn’t walk, because he’d lost both his legs. Whether that happened Before or After, nobody knew, because he didn’t like to talk about it, and if you pushed Simon on something he didn’t like to talk about he usually started screaming.

He claimed he had Asperger syndrome. When we first met him most of us just thought he was crazy. A lot of us still thought he was a drain on our resources, which is one thing we don’t normally forgive. But Vance had refused to leave him behind when we headed south from Scottsdale. Said he would come in useful, eventually.

Lucky guesses like that were what made Vance our leader. Simon, it turned out, had a way with machines. He could take them apart in his head and figure out why they didn’t work, and how to fix them. He’d put a truck back together from spare parts back at Scottsdale and that was the only way we got out of that hell alive. The truck had brought us all the way here before it ran out of gas and we couldn’t find anymore. When Vance found the motel, with the little creek running behind it, it was Simon who figured out how we could pump water up from the creek and survive in the desert.

Just looking at Simon, you would never believe it. He was maybe fifteen years old. He had a mop of black hair that hung down over his eyes. He was overweight, even after a year and a half of eating no more than I had. His fingers were pudgy and short and the nails were always cut down so far his fingertips bled.

With a couple dozen yards of PVC pipe, though, and some parts from the empty swimming pool’s pumps, he gave us running water. He gave us water for cooking, and washing, and even cleaning our clothes. He gave us water to drink in a place where you could die in four hours without it.

When I walked into reception he was fiddling with an old clock radio from one of the rooms, picking at a circuit board with those non-existent nails of his. “I wanna build a radio transponder,” he said. “So’s the Army can find us. I wanna build a computer so we can get back onna innernet.” In many ways Simon still lived in the Before—or maybe he just took the extremely long view, and assumed that this wasn’t the end of the world, just a momentary pause in civilization. “I wanna check my website, check my traffic. Traffic—traffic, we can get the traffic lights back on.”

Vance stepped out from the back office and nearly tousled the kid’s hair. He stopped himself before he actually touched him—Simon does not like to be touched. “Don’t worry,” Vance said. “You and me, buddy, we’re going to rebuild the entire world together.”

Simon looked up with an idiotic smile on his face. “I like to build things.”

Vance smiled back. “Darcy,” he said, turning to look at me. “You have something to report?”

He probably already knew what had happened out at the fence. Bruce and Finster had probably already let him know. But he wanted to hear it again, from me. Vance is not a big guy but you can see in his eyes that he’s always thinking. He’s always two steps ahead, which is how he keeps us alive. Nobody ever voted for him to be leader, and he didn’t have to fight anybody for the right. He led us because he was always on top of things when the rest of us were just trying to survive. “One dead guy, out by the southwest fence. I got him with an arrow.”

Vance nodded. “And did you retrieve the arrow?”

“Yeah,” I said.

He nodded and reached over to touch my arm. Most guys I’ve known, they would have grabbed me around the waist, or maybe patted me on the shoulder if they were trying to be PC. Vance squeezed my bicep. “I hear he was going for Candy.”

I shrugged. “Not anymore.”

He gave me another squeeze, on the strongest part of me. Like he knew. Just somehow he knew what was inside of me, and he approved.

A guy like Vance, back in Before? I wouldn’t have bothered giving him a second look. Now I’d move into his room if he just asked.

“Three this month,” Simon said, his face curling up. He looked like he might start screaming. “Three: one, two, three.”

Vance frowned. “That’s right,” he said. “More than we’re used to.”

I shrugged. “Some months we don’t see any. Sometimes we get a few. We can handle it.”

Vance nodded, but his brow was furrowed and I knew he was thinking of something. He went over to the drinking fountain that Simon had rigged up to be our main water supply. An inch-wide pipe stuck up out of the top of the box, and there was a crank on the side that pulled the water up from the creek. Vance started turning the crank but you could see on his face he was still thinking. “Simon,” he said, “is there any way to make that fence stronger?”

The boy started bouncing up and down in his chair. “Yeah, lots of ways! I wanna sink the posts in concrete, and double up on the chain link, and uh, and uh, we could ’lectrify it if we had some solar panels, and there’s barbed wire—”

He stopped suddenly, which wasn’t strange for Simon. Sometimes he just stopped talking and that was it. He would be silent for the rest of the day. Sometimes it was just a pause while he worked something out in his head.

This time he started screaming.

Vance was still winding the crank. You had to pull hard to get water out of the little trickle of the creek, and sometimes pebbles got in the pipe and you had to crank even harder. This time Vance was really working it, his arm flashing around and around. He’d been too preoccupied to notice why he had to work so hard. Something was in the pipe, something bigger than a pebble.

When he heard Simon scream, he stopped cranking—and then everybody saw what set Simon off. A human finger was sticking out of the top of the pipe, gray and mottled and topped with a broken yellow nail.

“Don’t throw up. Don’t do it,” I said, rubbing Finster’s back. When your entire food supply is comprised of tin cans you scavenge out of abandoned dollar stores, you can’t afford to waste a meal. Finster was looking green and starting to double over. Slowly he straightened up and started breathing deeply.

“Thanks. I just—ulp.” He closed his eyes and turned away. Simon kept screaming. Sometimes when he got that way he wouldn’t stop for hours. This was a kid who used to freak out when his father couldn’t find the right brand of chicken tenders for his dinner. The new world was full of triggers, and not a lot of comfort.

Vance grabbed the finger out of the pipe and shoved it in his pocket so nobody would have to see it. “Mike, Joe, I want this system taken apart and all the parts boiled until it’s sterile,” he said. The two men he’d named rushed over to the water fountain to start disassembling it. They were good people and they didn’t wait until things had calmed down to get to work.

“You okay now?” I asked Finster. He’d gotten some of his color back.

“Yeah. But—”

“What?” I asked.

“That thing. That—finger. It means—”

Bruce shook his head. “It doesn’t necessarily mean anything. The creek out back flows all the way from Tucson,” he insisted. “Some dead guy just lost his finger off the side of a bridge, that’s all.”

“—or it could mean there’s a horde of them downstream, splashing around in our water supply,” Finster said.

Everyone looked at Vance. Even Simon stopped screaming long enough to hear what our intrepid leader would say.

He glanced around the room, making eye contact with each of us. Then he shrugged. “We can’t afford not to know for sure. So we check it out.”

One of Vance’s rules was that nobody ever went outside alone. When he decided to form a search party to go check out the stream, he took almost everybody with him. There were miles of canyons and gullies to check out, washes that could hide hundreds of the dead from view that had to be explored. In the end he left only a handful of us behind. Finster and myself, to stand watch and to coordinate the search via radio. Simon, whose wheelchair couldn’t make the trip. And, of course, Candy. Candy never left my side.

The morning they left he had me do a radio check for him. Simon had rigged up a solar charger for a set of walkie-talkies we found in an overrun police station, and the radios had gotten us out of some pretty tight spots. We depended on them, but we didn’t trust them—you couldn’t really trust any technology from Before that relied on electricity. So Vance went up to the top of a hill about a quarter-mile from the hotel, while I went behind the motel’s detached laundry building and waited for him to call.

“Are you getting this?” he asked, and I confirmed. “How about now? Good. So we should be back in three days. If it takes longer, I’ll let you know.”

“I’ll be listening,” I told him.

“I don’t think we’re going to find anything. If that’s the case, it’s still a good excuse to do some foraging, turn up some more cans of food. You sound worried.”

“Do I?” I asked. I was surprised. I’d been keeping my voice very carefully casual. “I guess I’m always going to be concerned, when we split up like this.” That was one of the first things I’d learned, when this all began: Stay together. Let other people watch your back—you’re going to be busy enough watching your front. People who could work together, good people who cared about each other, stayed alive. People who couldn’t get along or who wanted to go it alone got weeded out pretty fast.

“Don’t be. We’ll take the guns, and there’ll be enough of us to take care of just about anything. You know I wouldn’t put any of us at risk unnecessarily.”

“I know.”

“I have to say I’m glad you’ll be back here, safe. Though, listen—Finster has said some things, when you weren’t around. Well, a lot of the guys have. But when you’re alone with him, he might try to take advantage of that fact.” “I’m not following,” I said. “I know you can take care of yourself, but… he might… offer his services, if you catch my drift.”

I laughed out loud. I couldn’t remember the last time I’d laughed. “Well,” I said, “in the absence of a better offer, maybe I’ll take him up on that.”

Vance laughed then, too. “Okay. Just make sure one of you is always watching the fence.”

The conversation ended there because we didn’t want to drain the radio batteries.

An hour later, the search party left, heading out through the big gate in the fence while Finster and I waved from the roof of the reception building, both of us covering their exit. Vance and his group took all of our guns, but I had my bow. I watched them go for hours, winding in single file down the road that ran alongside the creek, Vance marching along tirelessly at their fore.

“When are they coming back, Mommy?” Candy asked. I had her in a makeshift papoose on my back.

“Real soon.”

“We caught a couple of them today, working their way up the creek,” Vance said over the radio. “They were eating weeds and cactus, anything they could find.” He sounded tired. He’d been gone for only a day but already he’d covered ten square miles. He was pushing himself and his people hard, which made me nervous. “Honestly, Darcy, I didn’t expect to see even one out here. But I’m worried these might just be stragglers from a larger group.”

“How so?” I asked. I spooned cold baked beans onto a plate for Candy, the walkie-talkie cradled between my ear and my shoulder.

“One of them was wearing a business suit. One sleeve was torn off but his tie was still knotted around his neck. He didn’t look like a rancher or a tourist. He looked like somebody who belonged in a big city. I’m worried that we’re seeing people from Tucson.”

I stopped what I was doing and put down the spoon, careful not to spill any food. “That—would be bad,” I said.

When it happened, when the dead came back to life, most people in this part of the country lived in the big cities. There were millions of them packed into small geographical areas. That just meant that when the end of the world came, there was more food for the dead. They rarely ventured out into the desert, which is why we had made our home there. But we had always considered the possibility that the city dead would eventually exhaust their food supply and start wandering out into the country looking for more. The dead are always hungry, and they don’t sleep.

“It’s too soon to start panicking,” Vance told me. “How are things back on the home front?”

“Fine,” I said, steeling myself. He was right, there was no need to get worried—yet. “Finster’s been a perfect gentleman. Simon took apart the cash register and now it’s in pieces all over your office. He says he wants to build an electric water heater so we can have hot showers.”

“It would be nice,” he sighed. “All right. I’ll check in eight hours from now.”

“I’ll be listening.”

Candy picked up a finger full of beans and put it in her mouth. I watched her face, curled up in concentration. She was still learning such basic things—like how to feed herself. I smiled and she smiled back, then ate some more.

I stood the next watch, during which nothing happened. Candy played quietly while I walked back and forth on the roof of the motel, making long circuits from the rooms back to the reception building to the poolhouse, keeping my eyes open, keeping moving so I didn’t fall asleep. The red rocks beyond the fence never changed, and nothing moved. A breeze picked up for a while, which was kind of nice.

When my watch ended, I sank down in a folding chair and sucked some water out of a bottle. Finster climbed up behind me and just stood there for a while, not saying anything, just looking out at the horizon. I wondered if he was looking for Vance, the way I had been for hours.

Then he put his hands on my shoulders and started to rub. “You’re tense,” he said. “Worried about them?”

“Yeah.” I reached up to push his hands away. Then I stopped myself. If something happened, if Finster made a pass, would that be so bad? It would help pass the time. And it had been a very long time since anyone touched me like that. There had been a time when I’d gotten too much male attention, when it had been a drag. But that was Before.

It wasn’t like Vance was responding to my veiled hints, after all. I started leaning my head back, eyes closed, letting things happen. The tension of eighteen months started draining out of me.

Which, as we all know by now, is exactly when the bad things happen. This time, it was the radio squawking. I sat up straight and grabbed for the walkie-talkie.

“We’re coming back fast,” Vance said. There was a lot of static and he was barely whispering, but my heart raced as I made out his words. “Get everything you can into the backpacks. We’re going to have to bug out.”

“What did you find?” I asked, whispering myself. Behind me Finster crouched down to try to hear better.

“About fifty of them, all coming up the same canyon. They’re spread out pretty loose, and I think I haven’t seen them all. There’s probably more. Probably a lot more. This is Tucson. Go, now. Get things ready—we won’t have time to pack when I get back.”

“Understood,” I said, and signed off. I turned to face Finster. His face was as white as—well, as white as a dead guy’s. “Let’s move,” I told him.

We cracked open one of the motel rooms we used as cold storage and found the back packs waiting for us on an unmade bed. Ten of them, still half-full of stuff we never bothered to unpack. Bottles of purified water, bags of beef jerky and boxes of hard crackers. Canned food is heavy and if you’re carrying your supply on your back it slows you down. Into each pack we put survival gear, camp stoves, thermal blankets, first aid kits. Knives, lots of knives and other basic weapons. As much water as we could shove into the packs. If we were going to walk across the desert until we found another safe place we would need a gallon per day per person. There was no way we could carry enough, but the supply we had would just have to do.

Finster and I didn’t talk while we worked. Candy was slung on my back, fast asleep. She learned how to do that very early on. When Mommy’s busy, you just go to sleep—that’s a survival strategy. Good girl.

I didn’t feel bad about having to abandon the motel. It had been a good place, a shelter in a dangerous world, and I had no idea where we would find anything like it again. But the rules of this world are very clear: When you have to move on, you go and you don’t look back.

The search party had taken all our guns, which wasn’t saying much—they had two revolvers and a .22 pistol between them, and enough ammo to reload once. I had my bow and my quiver and Finster had a slingshot, a high-tech geek toy that could put a ball bearing through a dead guy’s skull at twenty yards. We geared ourselves up and hauled the packs out to the motel’s courtyard so the search party could just grab and go.

It was only when all that was done that I realized neither of us had been watching Simon. Nobody would expect the boy genius to help us get ready, so I guess we just ignored him until it was time to get him prepared for the move. Vance and Joe, the two strongest men in our group, had a kind of stretcher they had built so they could carry Simon around. It even had a little canopy to keep the sun off of him. Simon hated the thing, though, and we never brought it out until it was absolutely necessary. Just seeing it would be enough to trigger one of Simon’s screaming fits.

“He’s probably in reception playing with the cable box, wondering why he can’t tune in The Brady Bunch or something,” Finster said, when I asked where Simon was.

“You check there. I’ll look in his room,” I told him.

But he wasn’t in his room. Finster shouted to say he wasn’t in the office, either. I jogged back and forth across the parking lot, calling him, but got no response. He didn’t seem to be anywhere inside the fence.

Then I spotted him, and I nearly yelped in horror.

He was outside the fence.

Lord knows how he made it all that way, crawling around on his arms. He had the gate open and had crossed both lanes of the highway beyond. There was a stoplight out there that hadn’t worked since Before, with a big electrical junction box at the base of its pole. Simon had the box open and was pulling wires out, making neat piles around him sorted by color. I called his name but he didn’t even look up.

“Damn it,” I said, exasperated. This wasn’t the first time Simon had put us in danger, and I doubted it would be the last. I ran over to him, my heart pounding the second I was outside the fence, even though there was no sign of the dead in either direction. I tried to grab his arm and lift him up but Simon just went limp and his arm slithered through my hands. “Simon, come on, we have to go.”

“Busy. Busy building,” Simon said. “Vance says I can build. Vance says you have to leave me alone while I’m building.”

“Sure,” I tried, “but right now we need you to build something inside the fence.”

“I’ll do that later,” Simon said.

There was nothing for it. I just didn’t have the upper body strength to pick him up and carry him, not when he was going to fight me. I needed to get Finster to help. So I hurried back toward the gate, shouting for Finster to come help.

I don’t know if he heard me or not. He was pretty busy just then.

Tucson had come for us.

Hundreds of them. Maybe a thousand.

I hadn’t seen anything like it since the last days of Vegas.

Their clothes hung on them in tatters, and their flesh had shriveled on their bones. They must have run out of food in Tucson a while back and desperate hunger had driven them this far. Their eyes were cloudy with sun damage and their skin was covered in sores. Many of them were missing limbs, or at least fingers, but they all had their legs intact. When I saw them I understood what had happened. The fifty Vance had found in the canyons were the slow ones, the ones that didn’t keep up.

This was the crowd that could still move at a good clip. The ones that were still mostly healthy, who had gotten ahead of the rest.

You always expect them to be an unruly mob, shoving at each other and snarling at the ones who would rob them of their food. It wasn’t like that, though. They were barely aware of each other, but all of them wanted the same thing. They knew Finster and I were inside that fence. They moved in concert, pushing forward all at once. Never making the slightest sound. It was easy for the dead to take us by surprise, because they were as silent as the grave.

They hit the fence like a human tsunami. That side of the fence had been the strongest part—we had reinforced an existing fence there that had been made to keep out coyotes. The dead had no trouble with it at all. It came jangling down and they climbed over what was left.

Finster was working overtime with his slingshot, firing his giant-sized BBs one after the other, grabbing them out of a sack on his belt. He was a crack shot with that thing and he didn’t hesitate, but he didn’t waste shots either, making sure every round he fired was a clean head shot that took down his target.

I could have run up and joined him, and fired every single one of my arrows into that crowd in the time we had. Even healthy dead people move slow. I could see right away it was pointless, though. Neither of us had anything like enough ammunition. “Finster,” I shouted, “stop—you can’t get them all!”

“You have a better idea?” he asked me. His eyes looked crazed and I thought he might be hyperventilating.

“Yes! Come on, this way.” I grabbed at his arm and he followed.

“Come on. The reception office has the thickest walls, and we can get a couple of doors between us and them,” I told him, dashing around the side of the pool’s pump house. The dead were hot on our heels but we had no problem outrunning them. I rushed out onto the pool deck with my bow in my hand, an arrow already half-nocked. Good thing, too, because a dead woman in a pantsuit was already there waiting for me. She came stumbling toward me with her arms out, like she wanted to give me a big hug. I put my arrow right through her eye and jumped over her as she collapsed.

“But what then?” Finster demanded. “We just wait for them to go away?”

“No! We wait for Vance and the others to come rescue us,” I told him. Why couldn’t he see what we needed to do? I saw a dead man wearing a police uniform come stumbling through the weak part of the fence and shot an arrow through his forehead. “Just stick with me, Finster. We’ll be okay if—”

Finster screamed. The dead woman I’d put down was still moving. She had grabbed at the leg of his pants as he stepped over her.

He kicked at her furiously, even as her teeth came closer and closer to his flesh. One bite and it was all over—nobody ever survived a bite. I nocked another arrow, but couldn’t be sure of hitting her the way Finster was jumping around.

“It’s okay, I’m okay,” he shouted, as he stumbled away from her. “She didn’t get me.” She was still crawling toward him so I put another arrow in her ear. That stopped her. “I made it,” he said, gasping for breath. “I—”

He wasn’t looking where he was going. So happy that he’d escaped a fate worse than death, he didn’t watch his step, and he fell into the pool.

I rushed over to the edge of the pool and looked down. He’d fallen into the deep end and he was crying in pain. One of his legs was bent the wrong way.

“Finster, come on, get up!” I shouted at him, and he waved one hand at me to indicate he just needed a minute, that he would get up any time now.

We didn’t have a minute. The dead were streaming around the sides of the pump house, coming straight for us. I felt Candy stir against my back as she woke up. Why couldn’t she just have slept through this?

I should have left Finster there, of course. That’s how it was supposed to work. If you couldn’t walk, you couldn’t survive. But then, Simon couldn’t walk, either. Vance had changed some of the rules. He’d changed who we were. He’d made us into good people again. Given us something to live for.

“Take my hand,” I shouted at Finster, thrusting my arm down into the pool. “Take my goddamned hand!”

He blinked away his tears and struggled to get up. When he tried moving his broken leg he screamed in agony. I looked away to check on the dead. They were very close now. Before I could look back at Finster, he reached up and snagged my arm. I hauled him upwards, pulling so hard I thought my arm might come out of its socket. He got his free hand over the lip of the pool, though, and helped me pull him up.

“Stand up. Lean on me. We have to run, now,” I said, once he was out of the pool. “Think of it like a three-legged race, okay?”

He didn’t say anything. His face was a mask of pain. But he hopped on his good foot, his arm clutched tight around my shoulders. We were still faster than the dead.

Inside the reception lobby it was dark and cool once I closed all the window shutters. The dead hammered on the steel core door from the outside, their fists banging away at the wood veneer. It was holding, for the moment. I locked it, though I doubted any of them were smart enough to try to turn the knob. Then I headed into the back office, where I’d left Finster and Candy.

I barricaded the door of the reception office as best I could, shoving furniture up against it in a way that might slow the dead down for a minute or two. Candy had fully woken up by that point and wanted to know what was going on.

“Nothing, honey, we’re safe,” I told her. And she believed me. It’s amazing how trusting a three-year-old can be.

I had Finster laid out on the desk, his leg propped up on a pile of old file folders. There was blood on his jeans. That could mean one of two things. Either when he’d fallen his leg had suffered a compound fracture—which was very bad—or that he’d lied when he said the dead woman hadn’t bitten him.

Which would be a lot worse.

The only way to find out was to take his pants off, which I didn’t have the time or the steady nerves to do just then. I shoved my back up against the wall farthest from the door and sank down to sit on the floor. I just needed to calm down. I just needed to breathe carefully. This didn’t have to be the end for us. We could survive this.

I wanted to cry. I wanted to scream and bang on the walls with my fists, and shout for the dead to go away, and tear my hair out, and curl up in a ball, and throw up in horror. I didn’t do any of those things, because Candy was watching me very closely.

I could have been a good actress. I could have won an Oscar.

“Darcy,” Finster said, his breath coming in ragged spurts, “I want you to know something. I want you to know how I feel, since I may not get another chance, and—”

“Save it,” I told him. Which was maybe a little cruel. But I couldn’t afford to hear what he was going to say.

I pulled the walkie-talkie off my belt and checked the battery. Still about twenty minutes of talk time left. “Vance,” I said. “Vance, if you can hear me, come in.” There was no response, so I waited a minute and tried again. After that I waited five minutes before I tried a third time.

Meanwhile I could hear the dead in the lobby. They’d gotten through the door somehow. They didn’t make any noise but I could hear it when they knocked over furniture or crashed into the walls. How long did we have?

Not very long.

“Vance, come in, please,” I said.

“Darcy? What’s going on?”

I closed my eyes and thought about how much I loved that man. This was the man who was going to save Candy. And me. And Finster. “Vance, we have a couple hundred of them here. We’re locked in the reception office and can’t get out. You have to come save us.”

“I can see them,” Vance said. “I’m about a mile away.”

“Oh, thank God,” I said. “Oh, thank you Jesus.”

“Stay with me, Darcy,” Vance told me. “Is everyone okay?”

“Candy and I are fine. Finster broke his leg, and it’s bleeding.” I didn’t want to say what I suspected, that he might already be dying of a bite wound.

“Understood. How’s Simon holding up?”

“Simon?” I asked. As if I didn’t know who he was talking about.

“If he’s screaming too much, just let him play with his electronics.” Vance was quiet for a second. “Why don’t I hear him screaming?”

“He’s not in here with us,” I admitted. “The last time I saw him, he was outside of the fence. Opposite the gate.”

Vance didn’t respond for a while.

“Vance, come in,” I shouted.

“I’m still here, Darcy. Just trying to save my breath. We’re moving fast. You say Simon is outside of the fence. Okay. That’s good.”

“It is?”

Vance sounded determined. Steadfast. “All of the dead are inside the fence. Maybe they didn’t see him there. Maybe they just think you’re the better meal, since there’s three of you.” He took his mouth away from the microphone, but I could hear him giving orders. “Joe, Bruce, Phil, get down there and get that gate closed—that’ll give us a second or two. Arnold, do you see Simon down there? Take Mary and just pick him up. Don’t stop if he fights you, just hold him still and pick him up. Yes, damn it. That’s exactly what I’m saying. No, we are not leaving him behind. We need him if we’re going to rebuild anything. If we’re going to have a future.”

“Vance,” I called. “Vance, what should we do? I don’t think we can get out of here without help. Tell me your plan.”

“Hold on, Darcy,” he said, and went back to issuing orders.

Outside, the dead started pounding on the office door. The furniture barricade jumped every time they struck. It was loud, very loud in the tiny office, and the air in there started to feel very stale.

“Vance, please. Tell me how you’re going to get us out of here,” I said.

The radio was silent.

“Vance. Please. Vance, you son of a—”

“We’re not, Darcy.”

I opened my eyes. Finster was staring down at me. The barricade started to fall apart.

“We can’t. We don’t have the numbers. If I tried, I would just get all of us killed. I’m sorry. We got Simon to safety, if it’s any consolation. He’s going to be a big help. He’s going to teach us how to build things.”

“That’s—no consolation at all! Listen, you stupid motherfucker, my baby is in here! My little baby. She’s scared, and alone, and—”

“Darcy, it has to be this way. We’re going to run away, and hope the dead don’t follow us. I think they’ll be too busy trying to get at you to notice. Thank you for that. Your sacrifice is going to let other people live.”

“My baby, Vance. My baby is in here.”

“Call me names. Tell me what an asshole I am. If it helps,” Vance told me. “I promise, I won’t turn my radio off until I know it’s over. But I’m sorry. That’s all I can do for you.”

“What is he saying?” Finster demanded. “I can’t hear him!”

“Mommy?” Candy asked. Three-year-old trust only goes so far, I guess.

I swore and screamed at Vance, then, used every nasty, obscene insult I could think of. Called him a prick. Called him impotent. Called him a traitor and a baby-killer. Thought up some new names just for him.

But I knew. Even as the barricade collapsed and the dead poured into the room—even then, I knew, he wasn’t a bad man.

He was good people.

But these are evil times.

Copyright 2010 by David Wellington